Richard Acklom Harrison in Hull

Richard probably left America in 1775. He then disappears from the records for nine years. Watson says that he became Collector of Customs in Hull in 1777, but this is not the case. Josiah Corthine had been Collector in Hull since the 1760s, and is still listed as such in the 1784 directory; he died in that year, and Richard took over, with the title of Water Bailiff as well as Collector. It is possible that Rockingham's influence was at work again; he had become Prime Minister for the second time in 1782. Had Richard been living with his parents? Even after getting the job in Hull he does not appear in the directories until after he bought his own house in 1801. We do not know when his sister Elizabeth joined him. Brother and sister both remained unmarried, and it is likely that Elizabeth only came to live with Richard when both their parents were dead.

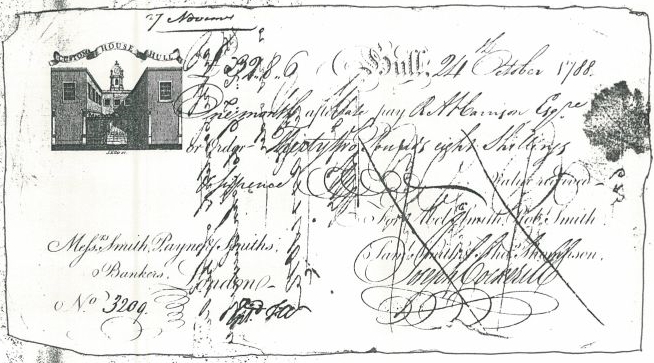

Richard got the job at a time when Hull was rapidly expanding as a port. The Hull Dock Company was formed in 1773. Created by the Hull Dock Act it was the first statutory dock company in Britain, and was responsible for the construction of the town's first dock, opened in 1778 and later re-named Queen's Dock. A bank was formed in 1784, Abel Smith & Sons (soon known as the Customs House Bank) to handle the remission of customs revenues to London. One of its first accounts was in Harrison's name, and a history of the bank records a bank draft dated 13 March 1784 to pay "R. A. Harrison, Esqre." the sum of £3.18s.8½d. A cheque exists, dated 1788, signed by Harrison.

He was paid £50 per quarter as Collector of Customs, and as Water Bailiff he received a percentage of the dues collected. He seems to have argued at some point that he should get more because the Bench decided in December 1792 that "two and a half per cent upon the amount of dues is a very sufficient allowance" for the work involved, and wrote to Harrison to tell him that these were the terms of the job and ask him "whether he chooses to accept them or not." He replied the following month accepting "without any further additional allowance". Harrison is listed in 1803 as owning one of the 120 shares in the Hull Dock Company.

| It was a time of greatly increasing trade, and Richard's income must have been rising as a result. In addition, the collection of customs was notoriously corrupt. Honest or not, Richard became rich enough to buy up several other properties in Salthouse Lane. He eventually owned the White Hart Inn, two houses with shops attached, a large tenement house, and the “family dwelling house” next door to his own home. Left: entrance to the 1778 dock, with Customs House at the right of the picture. |

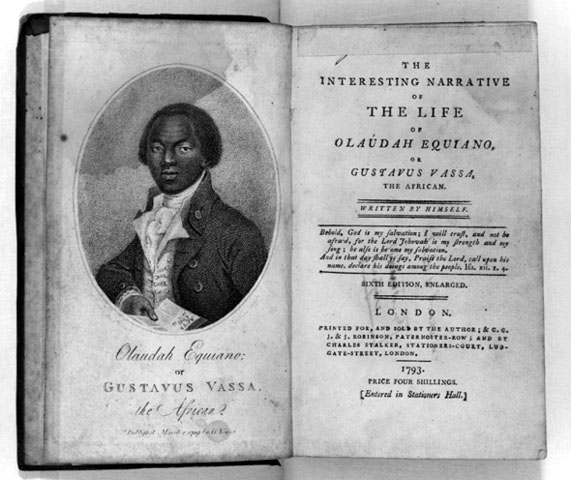

One of the few glimpses we have of Richard the man is the fact that on 12 November 1792 he signed his name, with the Mayor John Sykes and three others, to a letter recommending “Mr Gustavus Vassa, an African” to assistance in securing funds for “an interesting Narrative of his life”. This was the autobiography of Olaudah Equiano, the former slave who had taken the name of his Swedish owner, and in endorsing it Richard was stating his support for the abolitionist movement. |  |

The Capture of Henry Yorke

In June 1794 Richard was instrumental in the capture of Henry Yorke. Yorke, alias Redhead, was of West Indian birth and of mixed race. He was believed to have come from France to “sow the seeds of discord”, and had delivered a speech in Sheffield which had roused the population to something dangerously close to insurrection. His description was circulated to the chief magistrates of Liverpool, Newcastle, Sunderland, Shields, Hull and Carlisle to prevent him leaving the country. On 6 June he was reported to be in Manchester. On 14 June Richard wrote to Evan Nepean, Under-Secretary at the Home Office:

"I have learnt that he is at this moment in Lincolnshire – I have laid a plan of operations. Our Custom Ho. Cutter I despatched this morning for Lynn and given the Captain proper directions. Yorke gave out last Thursday Evng at Barton that he purposed going to Lynn – this I hope to be a Feint but for fear of accidents have secured that Port. I have hired a Pilot Boat under the [illegible] of a Party of Pleasure to [illegible]off in the Humber and board a ship bound for Hambro [sic] that sails from hence tomorrow and examine the Passengers when at sea, as I apprehend Yorke will not come to Hull where he is well known but be put on board from the Lincolnshire coast somewhere down the River near the Mouth. I am going myself into Lincolnshire this afternoon when the Tide serves to reconnoitre and I entertain [illegible] hopes that I shall have the honor [sic] of presenting him to you in the course of a few days. However my best exertions shall not be wanting in the service of my King and Country."

He signs himself “with great respect your faithful and most humble servant”. Nepean had been in charge of intelligence-gathering on Jacobin activity since the 1780s, and ran a network of spies in London. Clearly Harrison had spies on the south bank of the Humber and considerable resources to call on; perhaps he was part of Nepean's network himself. He seems to have relished the prospect of some action. On the same day, John Wray, the Mayor, wrote to report that Yorke had been seen in Barton, Lincolnshire, probably looking to join a ship for Hamburg, and he, Wray, was collaborating with Harrison with a view to arresting Yorke. They succeeded. The next day, Wray reported that Harrison had arrested the fugitive the previous evening and was taking him directly to London. Yorke was gaoled for over a year before being tried and found guilty. He was sentenced to a fine of £200 and two years' imprisonment. By the time he came out he had repudiated his republican principles.

Distributing Herring

In the late 1790s food prices had been rising steeply, and hunger caused riots in Hull, particularly in 1796. In the winter of 1800 / 1801 Richard and the Corporation complied with a government plan to buy up the glut of herring which had been landed in Scotland and distribute it cheaply to the poor. He organised a public subscription, securing a promise of £500 from Earl Fitzwilliam, and on 27 December 1800 he wrote to Fitzwilliam to report the success of this subscription. The Corporation gave £1,000; Richard personally gave £200. This enabled a “soup shop” to be opened in Hull for four days a week, to sell “most excellent meat soup to the poor at one penny” and fresh fish for three halfpence.

"This town and its immediate Neighbourhood will receive little aid from the Herring plan, but most considerable benefit is expected to be derived in the West Riding where the scarcity is much greater than with us, therefore it is hoped that the large towns of Leeds, Wakefield, Halifax etc. will improve on the example so generously set by the Town of Hull.2

Sadly, Richard had to report that he had received a letter from Leith saying that “Herrings have risen to three times their usual price”, but when they arrived they would be “forwarded up the River”. Enclosed with the letter to Fitzwilliam was a flier, issued by the Corporation, entitled “A Cheap, Good and Wholesome Article of FOOD, Fine Corned, or Sprinkled Herrings”. It describes the government's plan and extols the virtues of the fish and gives instructions on how to cook it.