The Liberty Incident

Joseph Harrison's appointment as Collector of Customs in Boston put him in an increasingly volatile situation. The hostility to the Stamp Act was exacerbated in Boston by what was called "customs racketeering", which the Americans saw as the confiscation of goods from the owners of small vessels and from individual seamen. In 1767 the Townshend Act made matters worse; it created a Board of Customs Commissioners under direct British control, and sanctioned searches by customs officials of homes, stores and offices. As a result of the Act, in 1767 three Customs Commissioners landed in Boston and attracted a great deal of resentment. Feeling threatened, the Commissioners called for military support, and on 17 May 1768 the 50-gun warship HMS Romney anchored in Boston. Its captain, short of crewmen, set about press-ganging local men. Matters came to a head in June with what came to be called the Liberty incident.

The story has often been told from an American perspective, with the blame placed squarely on the British. Joseph Harrison and Benjamin Hallowell, the Comptroller of Customs, had a rather different point of view.

| "The common people's anger came to a head on June 10th when commissioners used a customs racketeering technicality to seize John Hancock's merchant ship the Liberty. Although he possessed a well-deserved reputation for smuggling, for political reasons Hancock had curtailed his illegal activities. The commissioners did not, however, target him for his notorious smuggling operations; rather, they seized the Liberty because Hancock had spoken contemptuously of Customs Commissioners and because he was a highly visible member of the popular party" (John K. Alexander, Samuel Adams, pub. Rowan and Littlefield, 2004). This is now the accepted version of events. It does not quite chime with the earliest accounts. |

A package of documents was sent to the British government by the Commissioners on 16 June 1767; it included depositions from the leading characters in the drama. The first, taken on the day of the event, was from Thomas Kirk, a tidesman. He said that he had gone aboard the Liberty on 9 May to inspect the cargo before it was landed - a routine operation. The Captain, Marshall, had tried to persuade him to turn a blind eye to several casks of wine being taken off the ship i.e. they were being smuggled ashore. Kirk stated that he had refused to do this and was then forcibly shut up in the cabin for three hours. He had heard the noise of "a hoisting of the goods". His life had been threatened if he told what had happened, and so he had not come forward for a month - until, apparently, the ship again put into port. Hallowell and Harrison gave very similar sworn accounts of what happened next. Harrison, under orders from the Commissioners, had gone along to Hancock's wharf on the afternoon of 10 June, accompanied by Hallowell. Joseph's son Richard happened to meet them on the way and went with them. The Liberty had "lately arrived from Madeira". Harrison had arranged for a boat from the Romney to take charge of the sloop, which they seized from its Captain, Barnard. A crowd tried to prevent the seizure, and when the Harrisons and Hallowell returned to the shore they were set upon by the mob, which attacked them with sticks and threw stones. All three were injured, but it was 18-year-old Richard who got the worst of it. He swore that he:

"was surrounded and insulted by a numerous Mob, who pelted him with Stones and Dirt, and threw large sticks at him; they also threw him down and dragged him by the Hair of his head, and otherwise treated him in a cruel and barbarous manner, whereby he received two wounds, one in his leg and the other in his arm, and put him in imminent danger of his life, and had he not taken refuge in a House by the assistance of some friendly people, the Deponent verily believes that he should have been murdered, in the Street."

There were quite a number of "friendly people". Joseph Harrison and Benjamin Hallowell were also rescued. As the mob closed in on the Harrisons' house Eleanor and Elizabeth were taken to safety, and a group of men prevented the crowd from invading and smashing up the house. Frustrated, the mob broke the windows, then remembered that Joseph Harrison had a sailing boat in the harbour; so they wrecked and burned it.

Was this a deliberate targeting of Hancock's ship by the Commissioners for political reasons? Had Kirk been induced to give his belated account as an excuse to seize the ship? Joseph Harrison nowhere gives any indication that there was any such plot, or that he, as Collector, was doing anything other than applying the law. We do get a sense of a certain naiveté on Joseph's part.; but he was well aware of local feeling, and unhappy with the role of the Commissioners.

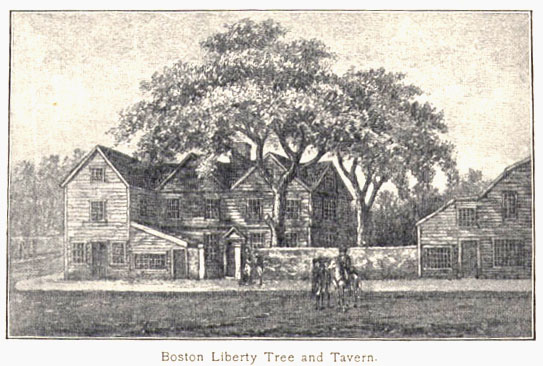

The Comissioners seem to have been at first insensitive and then frightened. They retreated, with the Harrisons and Hallowell, to the Romney and, after several days, to Castle William in the harbour. From there they requested military power to prevent "an open revolt of the Town". They complained that the Governor, Bernard, had done nothing (an accusation which Bernard vigorously denied) and wanted him to apply to General Gage for troops. They enclosed in their package to the Lords of the Treasury a letter which had been "stuck up in various parts of the town" from "The Sons of Liberty", calling a meeting "under the Liberty Tree" on Tuesday 14 June. The meeting went ahead, attended by about 2,000 people. |  |

On 17 June Joseph wrote a long letter to Rockingham from the safety of the Romney, moored off Castle William. He pointed out that he had warned about the trouble over customs duties, which had been building for some time, and the arrival of the Commissioners had made that worse. After Kirk's information, he had accepted the task of seizing the Liberty, despite being "so ill as to be just able to stirr abroad". He describes the violence of the mob and the injuries to himself, Hallowell and Richard (who is "in a miserable condition, being much bruised and wounded, tho' not dangerously, and I hope will soon get well again.") Joseph is particularly distressed about the destruction of his boat:

".... in all probability the mob would have dispersed if some evil minded people had not informed them that I had a fine sailing pleasure boat which I set great store by, that they lay in one of the docks, upon this intelligence the whole crowd posted down to the water side hauled the boat out of the water, and dragged her thro' the streets to Liberty Tree (as it is called) where she was formally condemned, and from thence dragged up into the common and there burned to ashes. The destruction of this boat I must own is a very sensible mortification she being as celebrated here for swift sailing as Bay Malton [one of Rockingham's race horses] is in England for running and had just before been nicely fitted out to send a present to Sir Geo. Savile."

He does not blame John Hancock, whom he likes but feels is being bullied by the mob into being their figurehead. Joseph found it "astonishing" that the Customs Commissioners had been sent out "naked and defenceless" after "the warning and experience of Stamp Act times" and while the Governor did not have the power to protect them. Benjamin Hallowell is on his way to England with the Commissioners' reports and will be able to answer any questions. Joseph goes into details about his ill health:

"The beginning of last winter I was in a fair way of recovering a confirmed state of health. But since the arrival of the Commissioners they have oppressed me with such a load of business, over and above, what related to the usual duty of my office that I have been worried and fatigued beyond expression which at last brought on the former disorder in my head and nerves. I was just recovering, and had got abroad again when this last unfortunate affair happened which has affected me so much that I am now as bad as ever. My present situation is indeed very distressing and truly pitiable. The Commissioners not very friendly (on account of my being an advocate for temperate measures till such time as the hands of government shall be strengthened) and the temper of the people such as to render it unsafe for me to be ashore, so that I am in a manner confined to a prison, which if it continues long must have a very bad effect on my health."

He ended the letter with a plea to be allowed to come home. He begs Rockingham to "engage some friend to apply in my behalf to the Treasury for leave of absence for twelve or even six months".

Joseph also wrote to his friend Sir George Savile, who told Rockingham about the letter at the end of July. He had also had letters from Richard, from Mr Acklom and from a Mr Constable "whose sister Mr Acklom married" but who he has never heard of. Mr Constable was in fact Eleanor's brother-in-law. The relatives of the Harrisons were obviously desperate for information, while Joseph waited for permission to return to England. Rockingham seems to have taken his time in replying. The archives contain a draft of a letter from him dated 2 October 1768 in which he expresses his "infinite concern at the disagreeable situation you are in." He has spoken to Sir George and to Mr Dowdeswell, and he believes that if Harrison were to come home, another Collector would be sent out. It would be politically difficult to justify his removal; if he came home he would be less listened to regarding the state of affairs in America and would be the object of resentment. "The anxiety you express in your letter at your situation makes it very irksome to me to give you the advice of still staying there." Rockingham piles on the flattery and assures Joseph that if he feels he must come home he will still have his "cordial friendship". He urges Harrison to keep the letter secret.